Saint Nicholas Orthodox Chapel

Kuivajärvi tsasouna represents the western style

In the second half of the 1700s, Karelian church architecture moved into a new style. The inspiration came from the new capital of Russia, St Petersburg, which was built in the Western style. Tsar Peter the Great (1672-1725) is known as a great admirer of the West, especially Germany and Holland. This is why the Karelian churches and tsasounas also feature a western tower on the building’s frame. However, the architectural basis of the tower is to be taken from the detached bell towers that were used in medieval shrines.

The Kuivajärvi tsasouna, completed in 1958, is architecturally representative of this westernised style. It is modelled on the village tsasouna of Ägläjärvi in Korpiselkä, which was destroyed in the recent wars. The current village tsasouna in Kuivajärvi is the third in the area. It is largely the result of the diligence of Olavi Lehmuskoski, a deacon who taught at Kuivajärvi school. The prayer house was consecrated on 28-29 June 1958 by Archbishop Paul, in Petruna. The tsasouna was built by the Finnish Orthodox Church on the basis of the Reconstruction Act of 20 January 1950, by the Finnish Construction Government, as the previous tsasouna had been destroyed during the war. Hannele and Tommi Niskanen were the hosts of the tsasouna.

Although the building tradition of the tsasouna dates back only to the 1700s, like the early history of the Kuiva and Hietajärvi village orthodox settlements, it is an excellent example of the carpentry skills of the men of the village. The well-kept trace of the work raises the same question that was raised by Hans Winfried Rohsmann, an Austrian professor and ethnologist who visited Kuivajärvi in the summer of 1976: what architectural value would this village have today if the dwellings were also in the old Karelian style?

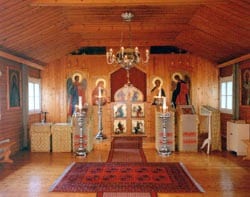

Iconostasis and holy icons

But the beauty of the Kuivajärvi tsasouna is not limited to its external charm. The sacred icons of the tsasouna were painted by the artist Martha Neiglick-Platonov. Designed by engineer Esko Aro and deacon Leo Kasango, the iconostasis, or picture wall, does not represent the Byzantine tradition of Karelian ecclesiastical architecture, the oldest stylistic tradition, characterised by the use of tempera colours and the placing of icons on horizontal mouldings on the eastern wall of the tsasouna. Icons could also be arranged in this way on several floors. This old tradition has been preserved in the village tsasounas of Hattuvaara and Saarijärvi in Ilomantsi.

In the 1940s, the knowledge of icons among members of our Orthodox congregation was still rather undeveloped, and many of them were unable to distinguish between a glossy Western-style painting and a spirited and refined icon painted in the old tradition.

Martta Neiglick-Platonov was one of our first icon painters who realised that we had to return to the old, authentic tradition and rediscover the Byzantine tradition of icon painting. Today we can admire his works in the Kuivajärvi tsasouna, which exude a wonderful richness of colour and the inner beauty of spirit that is the deepest expression of icons. The only exception is the icon of the institution of the Eucharist on the Holy Gate, which is ‘davinistic’ and unorthodox in its execution.

Altar Room

The so-called “Christ in the Hand” icon on the east end is the starting point of Christian iconography. On the left, behind the altar, is the icon of Christ Pantokrator, the most artistically valuable icon in the tsasouna. The Communion table is a beautiful piece of silverware from the 19th century, from the monastery of Valamo.

The Holy Table, or altar table, in the centre of the altar room, contains objects such as a silver chandelier, a censer, a chapel, a chapel of the Holy Spirit and a chapel of the Holy Spirit.

1) a communion clip (a panagia carried by an Orthodox bishop on his chest), which was also originally a communion clip in the early Christian period.

2) the altar gospel book. At the altar, no other books of the Bible than the Gospels are ever read, since Christ is the fulfilment of the prophecies of the Old Testament revelation. Other biblical texts are read in the chancel.

3) antiminsia (the name means “table counterpart” in Finnish and is a tradition of the early Christian Church, the episcopal mandate to conduct the apostolic liturgy, or communion service. The cloth depicts Christ being taken down from the cross and the four evangelists), on which the Holy Gifts are blessed and

4) the hand crosses used for the final blessings of the services, which are kissed by the faithful with the kiss of peace in accordance with biblical tradition.

Iconostasis or picture wall

An iconostasis is a wall of icons, or holy images, that connects the altar to the church hall. At the top of the iconostasis, above the Holy Door, is a small unorthodox ‘davinciman’ icon of the institution of the Eucharist. The icon’s central position indicates that the life of the church is centred on the celebration of the Holy Eucharist. At the doors of the Holy Door are icons of the four evangelists and an icon of the apparition of the Virgin Mary (Greek evangelismos = proclamation of the good news; a clearer expression of the content of the feast). The holy gate was originally the outer door of the church, in front of which the believers who participated in the Easter baptismal procession and entered the church from the baptismal font first shouted the Easter hymn: “Christ is risen! Then, as members of the Holy and royal clergy, they entered the church hall for the meal of the Kingdom of God, the Holy Eucharist.

In the 700-800s, the Holy Door became the central door of the iconostasis. The icons to the left of the Holy Door. At the north door, the High Angel Michael. On the altar table is an elaborate icon of Christ Almighty, painted in the 17th century and in the late Novgorodian style. Icons to the right of the holy gate: the icon of Christ Pantokrator (Almighty). In the south door, the High Angel Gabriel. Icons on the side of the nave: the icon of Christ the Forerunner, John the Baptist. On the right wall of the nave is the icon of St Nicholas. Icons on the side of the nave on the cold tables: an elaborate, miniature icon from the 19th century depicting the twelve great feasts of the church year, centred on Easter, the ‘feast of feasts’ in the Christian tradition. In addition to the traditional descent into Hades, the resurrection theme is also depicted with a Westernised theme of Christ’s ascent from the rocky grave. A special feature, which recalls apocryphal sources, is the ‘upturned eye of hell’ depicted in Hades, which illustrates the horror of hell after the descent of Life into Hades.Naturalistic and glossy icon of St Nicholas.

This Italo-German romanticism, combined with Slavic sentimentality, almost completely eroded the educational and ethical content of the old iconography in the 19th century. The icon became merely a creator of a vague atmosphere. Among the objects in the church hall, it is worth mentioning the foot candlesticks for incense from the monastery of Valamo. Originally, the incense and the lampstand were lamps used by the early church in the catacombs. Now the flame that burns on them speaks of the warmth of divine love. The table of remembrance of the dead, on which the faithful place the ashes, and in the vessel on which they place the grains of wheat, according to the words of Christ. The Orthodox tradition has preserved the Old Church belief, growing out of Christ’s resurrection message, that death does not mean the extinction of life, but that “rest in God” means the continuation of communion. This is most profoundly expressed in the Easter proverb: ‘Christ rose from the dead, conquered death by his death and gave life to those in the tombs’.

Next to the Tsasouna is the Domna Pirtti, built in honour of the Karelian building tradition. It has also been named as a memorial to the Viennese poets. It is named after the poet-singer Domna Huovinen.